Digital technology now dominates the world of photography, but around the edges there are still professional and amateur photographers who love using film. Rob Ditessa talk to three passionate film users and find out what drives them.

Dale Neill says, "I really thought this was magic happening before my eyes." He is recalling the first time he saw a print emerge from a developer tray. "Even after all the thousands of prints I've processed, I still think it's magic, the fact you can create an image on a bit of plain paper."

In his more than 50 years of photography, he has revelled in the magic of film with students as a teacher at TAFE and University of Western Australia, and shared its results with clients in the fine pictures he has made in his professional photography business.

And today an increasing number of photographers, and newcomers to the craft, want to enjoy the magic of that experience of capturing an image on film and then developing and printing a picture. There is a resurgence of interest in film photography, Neill says. When he walks down the street with a film camera around his neck, he says enthusiasts who know see him working with it and come up to him to ask about it, and about film. Some enthusiasts, he says, believe that film has advantages. 'Novelty' and 'quality' are two factors Neill puts forward for its resurgence.

Escaping Hen, by Dale Neill. Nikon F90, Nikkor 24-70mm zoom on Fuji Provia 100, ISO 100.

Chris Reid, from the professional film processing and printing practice Blanco Negro in Sydney, suggests people – especially the younger ones – like getting away from computers and screens to take pictures with film cameras. He thinks they like the look of the unexpected. With digital you always know what you're getting, whereas when you shoot film, you do have the odd unexpected result. As well, some older photographers who 'went digital' are now coming full circle back to film. It makes them better photographers, Reid says, because they have to double-check everything. When they can't see what they have in camera, they must make sure they nail the photo. When you check a contact sheet, Reid reflects, the 'hero' shot instantly jumps out at you, rather than all the images on the computer screen starting to look the same. Photographer Chris Peken sees some correlation between the resurgence of film and the emergence of the 'hipster' culture, with its interest in vintage objects and styles. He also points out that film has always been used in high-end work.

There is a trend, according to Neill, for new film enthusiasts to buy their cameras and film and shoot, but not process the film or print the images themselves. Processing film requires a set of skills in itself, he explains. To get a result is straight forward enough, but to accurately interpret the original scene, and then adjust the type of developer, temperature and time to reproduce a full tonal range is a sophisticated process, before selecting and making the print. It's a pity new enthusiasts can miss out on some of the more technical elements, such as the principles of sensitometry when it comes to interpreting their negative, he says. As a result, he believes they miss out on experiencing the whole of the film process.

He thinks there's something special about film. At an exhibition he was judging just last year, Neill immediately identified three images he thought came from film. He was proved right!

"I could pick up on this subtle, but different quality. That's not saying it's necessarily better or worse, because if you're a lousy photographer and you shoot on film, that doesn't make you great. But I think there is a subtle difference. If you shoot on film, you've got a slightly larger range of tonal acceptance than you have off even the best digital cameras. With the point and shoots, you're getting about five f-stops, with the DSLR you're getting about 6, maybe 7, and off film you're getting about 7 or 8 f-stops. If you shoot on medium format, you get maybe 8 or 9 f-stops. So you've got an immediate technical advantage in that you're able to accept a wider range of tones when you shoot on film."

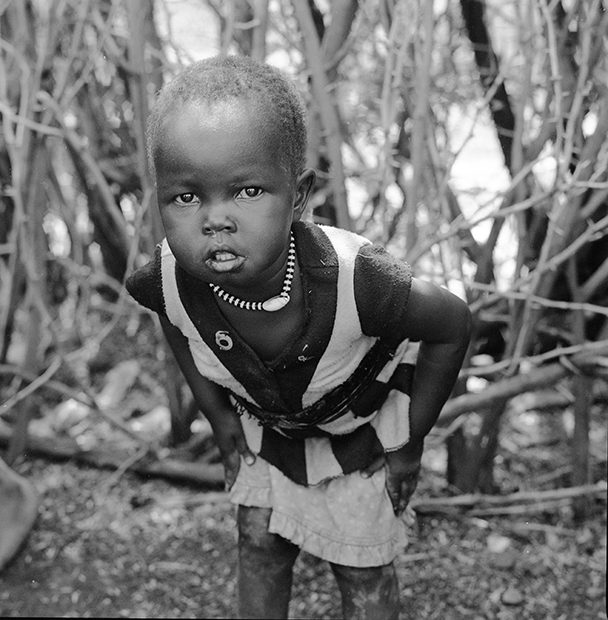

Turkana child, Kakuma, Kenya, 2013, by Chris Peken. Hasselblad 503CX, 80mm f/2 CF, Tri-X 400 at +1.

He cautions that colour film is more complex to handle because not only are you trying to print with correct density, but also with correct colour. It's a slower process which necessitates more control.

Matthew Sutton has been shooting since he was 11, when his father gave him a Kodak Instamatic camera. He taught himself darkroom techniques at school when he was 16 and that led to a job in advertising. Eventually, in 2000 he moved into digital, but within three years he sold every piece of his digital kit and returned to film, and while he takes colour shots, he prefers black and white.

Sutton has published one book of his own work, contributed to another, and has shown his work in a number of exhibitions. He finds enjoyment in the process of film photography, in clicking the shutter and knowing he has captured something, and in the crucial calm and patience required in processing and printing. Recently a number of young enthusiasts sought his mentorship in learning film and he steered them to doing research and work by themselves. They came back pleased with their negatives, and their discoveries.

That is what it is all about, he says, and whether you do all the work or a lab does some, the developing or the printing, it doesn't matter. In film there is a deeper truth, he believes. Film doesn't lie – unless you manipulate a scanned image! From his experiences he ponders the technicalities and techniques of film versus digital, and the emotional and personal elements involved. Sutton believes that film is better at capturing aspects of a scene, so a picture always reveals something for the viewer, and even the photographer.

New Zealand. Image by Dale Neill. Pentax 67, Takuma 105mm f/2.4 lens on Fujicolor Pro, ISO 400.

Peken is a photographer of 14 years standing who works in newspapers and magazines in Sydney, and who has photographed in various countries. His latest body of work, The Lost Boys of Sudan exhibition, won critical praise and a story on the ABC TV 7.30 Report. For his own work, black and white film is his personal medium of choice.

"One of the qualities of film is that it is inherently every frame is different. Film is composed of minute silver particles. They're never in the same spot. If you work digitally, a pixel is in the exact same spot in every frame that you take. There's an inherent random nature in film. Even if you can't see it, by the very nature of the film each frame will be slightly different, even if you were to take the exact same photo."

Using a film camera slows you down and frees you up, he says. Peken explains it slows you down because you can't shoot hundreds of frames each hour like digital; and unlike digital, film can take a long time before you see an image, especially if you have work which was taken overseas.

Hoi An, Market woman, by Matthew Sutton. Leica MP, 35mm lens, Kodak colour transparency EB3, ISO 100, 1/125s @ f/2.8.

Another point to consider is the cost of having to develop each shot. On another level, it also frees you up. With film you don't have to constantly look at a screen, or look at the image. You take it, it's gone, and then you can focus on the next moment without reference to the previous image. He reflects that the journey as well as the destination is different.

Students, Peken has found, have no real understanding of the relationship of speed, aperture and ISO, because when photography is done digitally, they don't need to worry about understanding it. Once he gives them an understanding, he finds that it informs their digital work as well. He says that an essential item in your kit is a light meter until you can read the light from experience.

Peken says it's essential that you trust your lab to develop and print your work, and he adds that for him the printing becomes a collaboration. He has input into the sort of look he wants to achieve, views the test print, and suggests changes, but he always trusts the advice he receives from the master printer he deals with. The film gear Peken uses is up to 70 years old, and he says it has a better lens on it than most of his digital gear.

"These cameras were hand-made. They require no batteries. The digital camera has a computer to tell it to shoot at 1/1000th of a second. This camera does it because of some cogs and some machinery that someone hand crafted, and there's something very tactile about the feel of pushing the button, feeling the shutter go, winding the film on. You are more connected to the process. It's a more meditative process to use film than digital."

Reid still does everything by hand in his lab. While there are a few others around Australia, they will do colour, and digital as well, he says.

"Most of them have combined all the different aspects of it, but commercially, I'm pretty sure I'm probably the only one with a dedicated black and white darkroom".

He also runs classes and hires out the darkroom. For the enthusiast, he says, finding a suitable camera and equipment is pretty easy. There are many affordable film cameras on the market because everyone has been upgrading over the years. As professional cameras were all mechanical, they are quite straight forward to repair, and they're very reliable.

"There's a wealth of lenses out there, and all the other equipment, but you have got to be a little bit 'savvy' about where you look. Forget about looking in Australia because there is not enough volume over here, whereas in the UK, in US, and Japan there's plenty. You can buy absolutely anything you want, but you do have to look for it."

New York street scene, 2011, by Chris Peken. Mamiya 6, 75mm, Tri-X 400 at plus 1.

Similarly, darkroom equipment is available and affordable. When it comes to darkroom chemistry, he says he deals directly with a manufacturer, Foma, for black and white material. Established in 1921, Foma has a large market in Eastern Europe where many photographers still use tried and tested film technology.

Neill can lay claim to still having every negative he has shot since he started shooting with film at the age of 16.

"I've never lost one, but I've lost digital images through hard drive failure and corrupt memory cards. I think this is one of the principle advantages of shooting on film, that the result is analogue, and that it's tangible. You can hold up the negative to the light, and say here is my image."

Film is really about having fun and communicating, says Neill. "The whole process should be enjoyable. I'd encourage any beginner to start thinking about printing, not just leaving the images on digital media, and then to start thinking about their first exhibition. Photography is a subjective experience and that can be shared objectively with others. Exhibiting your work is a great way to further communicate with people." ❂

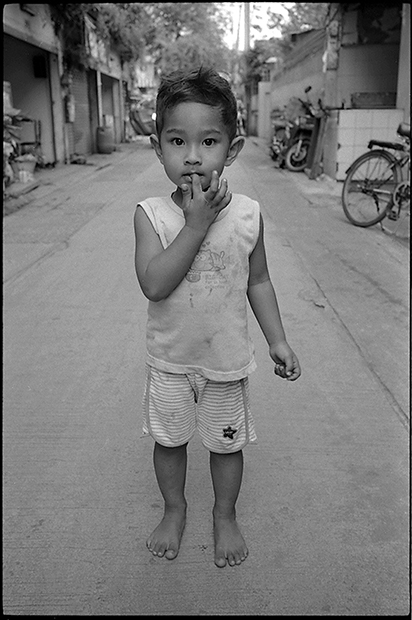

Bangkok, Little Street Boy, by Matthew Sutton. Leica MP, 35mm lens, Fuji

Neopan film, 100 ASA, shot at 1/60s @ f/5.6, developed in D76.