Q&A: Joel Meyerowitz

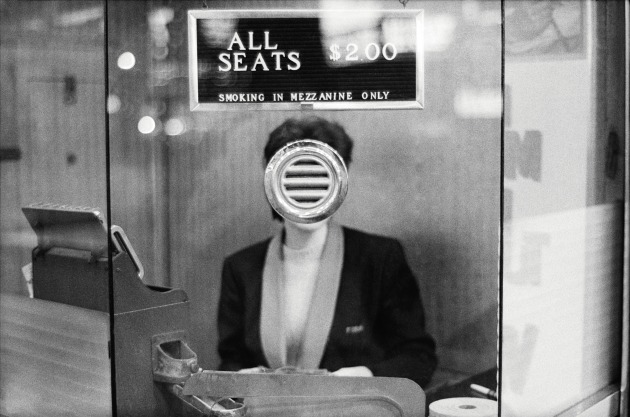

Considered by many to be the godfather of street photography, Joel Meyerowitz has spent a lifetime perfecting his craft. Now for the first time a retrospective book charts his complete career from wide-eyed apprentice to one of the world’s great living photographers.

A New York Times article once stated that to view the collected work of Joel Meyerowitz was to view a recent history of photography itself. While this statement might seem a tad hyperbolic, it actually isn’t as far fetched as it sounds. After all, Meyerowitz has spent the majority of half a century with a Leica in hand, re-writing what photography meant to both the fine art world and to society in general.

Some five decades after coming under the spell of Robert Frank and paving the way for street photography to be considered a legitimate art form, Meyerowitz’s new publication Where I Find Myself is the first major single retrospective of his work.

Organized in reverse chronological order, the book spans the photographer’s career, from his works on trees, to his coverage of 9/11 at Ground Zero, and finally ends with his iconic street images, but, as he insists, the new book is not simply a “best of”.

Yet whilst the book certainly serves as a comprehensive retrospective of one of the greatest photographers of all time, it also serves to chronicle the evolution of photography from the rigid, confined version of itself, as Meyerowitz discovered it, to the revered, colourful, insightful and joyous medium he turned it into.

Meyerowitz hopes the book will simply pose the question: “Can you see me?”, a line that cheekily hints at the philosophy behind his approach to photography.

Australian Photography: Joel, Five decades of photography is a long time! What changes have you witnessed?

JM: “It’s been 55 years that I have been making photographs. I started in ‘62 so it has actually been 56 years! And really, the arc of photography in the twentieth century—the rise of it from a kind of basement level characterisation—you know, it was’t in the museums as a significant art form, it wasn’t being sold.

I remember in 1964 going to see an exhibition of Ansel Adams’ work and the pictures were $25. And nobody was buying them. So, my friends and I thought there’s no hope for us.

We had to find another way to make a living while doing photography in a serious form; the way we thought it was meant to be. And I think it was my generation that started to push the medium forward against all the resistance that the art world had. And look where it is today, it has quite a strong parity with fine art or with painting.

I think watching that happen these 50 plus years…plus the acceptance of colour.

When I started, the first rolls of film I shot were colour because I didn’t have any understanding of photography whatsoever, but I knew that I wanted to try and make photographs on the street so I borrowed a camera, I bought some colour film and that was it.

My first shooting buddy was Tony Ray Jones. He was a graphic designer like I was at the time and somehow we found each other in the lab. We looked at each others’ dreadful, early photographs and somehow we just had the right spirit. We decided to go shooting together to try to learn about how to make photographs, how to be invisible on the street, how to be in the right place at the right time.

In that time together—the two of us, two guys in their early twenties talking about photography and talking about colour—I think what was so striking was that both of us were using colour in a way that no one cared about at that time. It seemed too commercial or too amateur, so in a way, we were pushing, and we could feel the resistance from the art world.

Whenever we would show our pictures they would say “why aren’t you shooting black and white?” And we would respond with: “Why would we? The world is in colour; we are going to shoot in colour.”

The darkroom was, and still is, the punishment of the medium. You had to go in there and spend long nights and days developing your body of work and your skill and your sensitivity to the medium. And nowadays people are more content sending you an email, putting it up on Instagram or something like that.

To me, I think you might get your work out there to thousands of people who will click the “like” button, but who knows if anybody is really paying deep attention to the work. It is such a generalised resource, these online depositories of photographs. I think there are certainly interesting changes; the audience is greater but not necessarily more educated.

Clicking a like button isn’t necessarily a critique, it is a casual “that pussy cat is cute or that is a really nice sunset”. I don’t see much of a dialogue between photographers, however [at the same time] there are lots of people who are doing podcasts and the like who are really getting down in there and being critical in the very best ways. So, I see it as a kind of mixed blessing between the mundane and the profound.

AP: You’ve mentioned how important it is for your process that you were able to experience shooting various formats (6x7, 8x10). Are photographers missing out on the benefits of that today?

JM: I’m grateful that I have had that desire to make the change - to experience something else because when I switched from 35mm to 8x10, I wasn’t shooting solely 8x10. I always carried a 35mm and I still do (although it is a digital Leica now).

When I made that switch, I needed something - I needed a particular kind of descriptive quality that would allow me to make very large prints.

This was in the early ‘70s when large prints were not part of the vocabulary of photography—people made an 8x14” print and that was sort of the standard form—Robert Frank, Gary Winnogrand. Diane Arbus was about 20 inches square, but everybody printed at this ‘hand’ size and because my argument for colour was strong and I was always projecting slides on the wall, I had the experience of big scope.

After all, 35mm film was being used for Hollywood movies so I thought “why can’t I make extraordinarily large prints with this film?”. However, when I tried, the quality wasn’t so great. So, in order to have greater descriptive power, I moved to the 8x10 format and of course when you make a move like that, it changes the way that you shoot because it is not a 35mm camera - you are dealing with a different beast.

I discovered that I had a second personality, in that instead of being this jazzy guy doing these little riffs on the street, I could also be more contemplative and slower and look at things from a perspective that was much more spacious. It was wonderful at the time to find I had this other side to myself and could make the enquiry in a genuine way without having to give up the other side.

So, it was like I had my own internal argument between what was the subject matter for an 8x10 and what was the subject matter for a 35mm. That period was a very expansive and very creative one for me. I was in my early 40s, so I had my curiosity, and my passion was intact and developing even stronger because it was like I was learning the whole medium over again.

Sometimes you just get lucky; you ask the right question and photography gives you answers that are surprising. A dialogue between the artist and the medium is essential.

Before I was a photographer I was a painter and lot of my friends were abstract expressionist painters. They were into the liquidity of paint, the way it ran on the canvas or whether you have to push it, smear it, shape it or squirt - I mean, the physical characteristics of paint and whether you put it on canvas or glass or whatever - that was part of the discussion because the actual moving material was something you had to investigate.

So, I think a discussion or an interaction with the characteristics of the medium should be no different for photography. Even though photography seems narrow—like a camera and printing paper—it’s more than that.

AP: What are your thoughts on truth and objectivity in photography today? Photojournalism in particular seems to be going through some kind of growing pains in this respect.

JM: One of the burdens that photography has always carried is that it was used to document and show things as they were. There was once a great show at MOMA called “Evidentiary photographs” - they were the pictures made in factories, and in laboratories when someone was shooting bullets into something or crashing cars or blowing things up.

The camera was used to document the way that things looked upon impact or upon explosion so that the evidence as recorded by the camera was believed. The camera was believed to tell the truth and it was used as evidence in court. Well, we have lost that now because with Photoshop you can eliminate the things you don’t want, you can add elements that you think enhance it. And this kind of flexibility or fluidity has been adopted by lots of artists in order to make their own newly-imaged worlds. As if the reality of reality is not good enough! It needs to be enhanced or modified in ways to make it art.

I come from that time that still believes in the authenticity of the moment. I don’t know about truth because you can photograph something but you’re looking at it head on. [While] someone else photographing it from ten feet to the left, looking at it on the oblique, is going to see things behind what you see and you can’t get in your picture. So, their version of that moment of truth is going to look different. So truth has always been flexible.

I don’t get too upset about [Steve] McCurry’s adaption because I have seen a couple of times when I’ve been working that the scene in front of me is changing.

So, I make the picture and just as I make the best moment, the frame isn’t as beautiful as I like it, but in a second I can make another picture because someone has walked into the frame. Believe me, I have thought a number of times “I was there! It just didn’t happen” but I could take the second picture and blend a piece of it into the first picture because it was a continuity - one thing happened but then another thing happened just a fraction of a second afterwards.

So, there is the sensation that I could do that. I don’t do it because I am of the belief that what you see and what you get is what you have to deal with. Even it is not perfect.

But someone in the field like McCurry or documentary photographers might want to extend the moment as if their lens was wider and they could grasp more. If it could enrich the reality of the moment so that we understand what was going on in a better way, there is something to consider there.

But I am of that old-school Cartier-Bresson school where you have to move to get that frame. Otherwise, you just have to say “oh well, I didn’t get it”.

I was just in Spain for an exhibition and the foundation which built their own museum collect a lot of Robert Frank’s photographs captured during his time in the country in the late 40s. They hung a huge contact sheet on the wall. So I’m looking at it and saying to myself “I know that picture but… he’s cropped it!”. And I said to the director who was with me: “I know that picture and there’s a piece of it that’s not in the print”.

So we went and looked at it in the next room and I would say that if it was a 14 inch print, that about two and a half inches was missing. It is a picture of an elevator operator. Frank had originally included the outside of the elevator where there was a person walking away, but in the print he cut it off so it looked like a 35mm format. Yet all our lives we thought that Bresson and Frank didn’t crop.

So, because of that, my generation thought that we couldn’t crop - we had to use the frame as it was. In a way I think we tend to misread something about the standards of our time and to adopt something about those standards as our law; our aesthetic law.

So I think the new aesthetic laws are stretching something about what we choose to put in a photograph. It changes the appreciation of the skill of the artist. For my generation, it wasn’t the quality of the print but something about the perception of the artist, because when you press that button for a 1/1000th of a second, you are working at the limits of your perception.

AP: Has the vast spectrum of editing options available to us today served to enhance or detract from the overall quality of photography?

JM: I think when there are too many options dangled in front of you and they are so rich in potential, so full of distractions - it is like when you have a box full of 40 chocolates and you can’t make up your mind.

But when people buy a single camera and commit themselves to it, they go deep into the system of photography that camera supports or offers in a way. And then they enrich themselves. I think it is the marketing structure of today’s world and how rich in possibilities it is, that makes it so confusing.

For me, the basic question of photography is: “what is your identity as an artist and how is it manifested in the photographs you make?”In one sense, everybody is generalising; a sunset, or a flower belongs to everybody, and you can’t tell who the fuck made that flower picture, but then you get some people who really go in and they find their identity in the flowers they choose. So, suddenly you realize “oh, this is a Mapplethorpe flower or an Irving Penn flower” because their identity is so powerful that they show you themselves no matter what the subject.

I think people are actually in search of their identity but they don’t quite know it. I have heard a thousand times: “I am so bored with my photographs” and it is because they are not discriminating, they are not entering into a dialogue with themselves. Yet they can but they don’t quite believe it.

AP: Can you tell us a bit about the new book? Did you employ your usual editing process for such a significant publication?

JM: The scope of this book is so large that my usual editing process didn’t quite work exactly the same way. In general when I do a book about a subject or a body of work, I make little card sized photographs so that I can shuffle the deck all day long and lay them out in runs because… here it is again: Robert Frank.

When I was a young photographer, the only book I had was The Americans. That book was so powerful and mysterious and the rhythms in it… I thought: one day, maybe I’ll make a book, because it is fixed in that order and you can read through it like poetry.

But how do you get to make that book? So, I would carry prints around and I would lay them out in order until I found one that had an interesting arc to it. Then, often when I had it all laid out, I would photograph them in that sequence, print it, fold it and put it together like a book in miniature to see how it held up on its own. In this new book, I did that with the chapters because I had to make it manageable in size.

I was talking to my wife about editing this book and I said “I just don’t feel like starting where I began because I’m at this point now where I am looking back through my own history and I can see how things line up. So, she said “start from the present! Work your way backwards”. So, I started putting in the pictures I am working on now then seeing how arrived there, looking at the pictures I made before. So, sometimes a little stroke of luck unfolds a little curiosity.

AP: What does this book mean to you? What does it mean to publish such a in-depth retrospective of over five decades of work.

JM: This book offered me that kind of opportunity to stand at a crest in the road and to look back over all the little hills and valleys and to consider how I got to where I am now.

So many times, we come to a crossroad and we decide to go left or to go right. And that changes your life, even if it is just a small decision. If you go east, then everything to the west you are never going to know.

Photography has done that for me: every decision I have ever made has brought me to where I am so in a way I wanted to try and store those sudden appearances of instinct and impulse because if you don’t follow your basic instinct then you are going against who you are.

I think it is important to validate and to de-mystify for the reader this quality of photography that depends on absolute instinct. We all make decisions that use instinct but photography requires the instinct of the moment. I think instant and instinct: these two things together give shape and direction to every photographer’s work.

What I hoped to do with this book was to lay out the cards on the table and to show what this kind of life—the curious life of a photographer—has allowed me to see.

So, it is an offering in that way. It isn’t the best hits of Joel Meyerowitz or anything didactic about how photography should be, it is just asking the question “Can you see me?” That is basically what I am asking.

AP: what do you forecast for the next five decades of the medium? Where are we going with photography, and how will it be used in the future?

JM: I’m not a prophet. I’m a realist living in the moment, but if you base a forecast on what has happened in the last 50 years, at least a billion people now walk around with a camera in their hands or their pocket every day.

It used to be that you had to buy a camera and to carry it. So, that was a decision that everybody made—not everybody wanted a camera—but everybody wants a smartphone and along with that comes a camera.

And what I see is that the increase in appetite is going to produce an abundance of new minds - fresh, original, young minds who are seeing the world through this telephone-camera instrument and whose appetite will be expanded, maybe enough to go and buy a real camera and to pursue the quality of life around them.

Really I think the most important thing is that we are going to have a larger amount of people entering the serious world of photography from a greater variety of backgrounds, bringing a new kind of energy to it. I think the boundaries of what is photographic are going to be enlarged in so many ways.

I am still grounded in a value system from the 20th century and I look to see that in other peoples’ work and how they hold onto those values of perception, but how they also moved into the present. That is my yardstick for when I look at new photographers: how they push against the resistance of the past, just like I pushed against the resistance of black and white by using colour. So, it is in the hands of the young, really. ❂